My Experience With Operation Airdrop

Oct 6, 2024

Introduction and Context

Disclaimer

I have been increasingly frustrated with the narrative online about what’s goig with Hurricane Helene relief efforts w.r.t. civilian aviation. This is my personal experience with flying an aid mission, I do not speak for anyone else or any organization, others may have had other experiences.

Why Light Aircraft?

Helene caused bridges to collapse and many roads to be washed away. Trucks are the most efficient way to transport supplies/goods, but only if they can actually reach the destination. As roads were being cleared or alternative paths being built, light aircraft are able to fly into more remote areas and deliver supplies. The United States has the largest civilian aircraft fleet in the world, and it’s beginning to be more common to leverage this fleet after a natural disaster.

The aircraft that I fly is designed for flight into short runways/strips, and can even be used for ‘off airport’ operations, so I decided I would try and help.

Context about Flying and Air Traffic Control

In aviation there are a few different ‘flight categories’. Visual Meteorological Conditions (VMC) mean that you are able to navigate by visual references to the ground, sky, and horizon. There are ‘objective’ standards by which VMC is judged, the visbility must extend a certain distance, the cloud ceiling cannot be too high, etc. Another common category is Instrument Meteorological Conditions (IMC), which means that flight cannot be accomplished by visual references and must instead be accomplished ‘by reference to instruments’ in the cockpit.

Those are the categories as determined by the weather, there are also regulations that determine how you need to fly (distance to clouds in different airspaces, do you need to be talking to ATC, etc.). You can fly by the Visual Flight Rules (VFR) only in VMC. You can fly by the Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) in VMC or in IMC. You might choose to fly IFR in VMC for practice or because of the additional support you get from ATC, etc.

Lastly, if you’re flying by VFR you often don’t have to talk to ATC unless you want to, you’re expected to ‘see and avoid’ other aircraft. If you want to, and if they have the capacity, it can often be beneficial to be talking to them as they see the bigger picture of who is going where and can help you avoid other aircraft/warn of know weather issues/etc.

Things were so busy in Western North Carolina that unless you’re part of the relief effort, ATC didn’t have enough capacity to talk to everyone that wanted to talk to them. At one point they weren’t even able to help with IFR flights, which means that if the weather is not VMC, you can’t take off and are stuck on the ground until they have the capacity to talk to you or the weather becomes VMC.

Relief Efforts in NC

Dispatch

So I fly down there Friday morning from DC. While I was still in DC airspace I tell ATC where I’m going, they know from context that I’m heading down to help with the relief effort. ATC was overwhelmingly accommodating. Every step of the way they were helping aircraft get to where they needed to go. When I got to the airspace near the relief effort it was busier than any airspace I have ever flown in.

The organization I’m working with has a supply hub, near Charlotte, that had been spared the worst of the storm but was still near enough to the Appalachians to fly supplies in where they are needed. By this stage of the relief efforts things were fairly well-oiled.

I land at the supply hub, they only asked three bits of information:

- My tail number

- the type of aircraft

- How much cargo (weight) I can take

Because the aircraft I fly is able to land in tighter spots, the dispatcher (person figuring out who should go where) asked whether I was comfortable going to an airport that was a bit trickier, and had therefore received fewer supply runs. My co-pilot and I spent some time looking up the airport; its runway lengths, its elevation, and determined that while tricky we were comfortable with the mission.

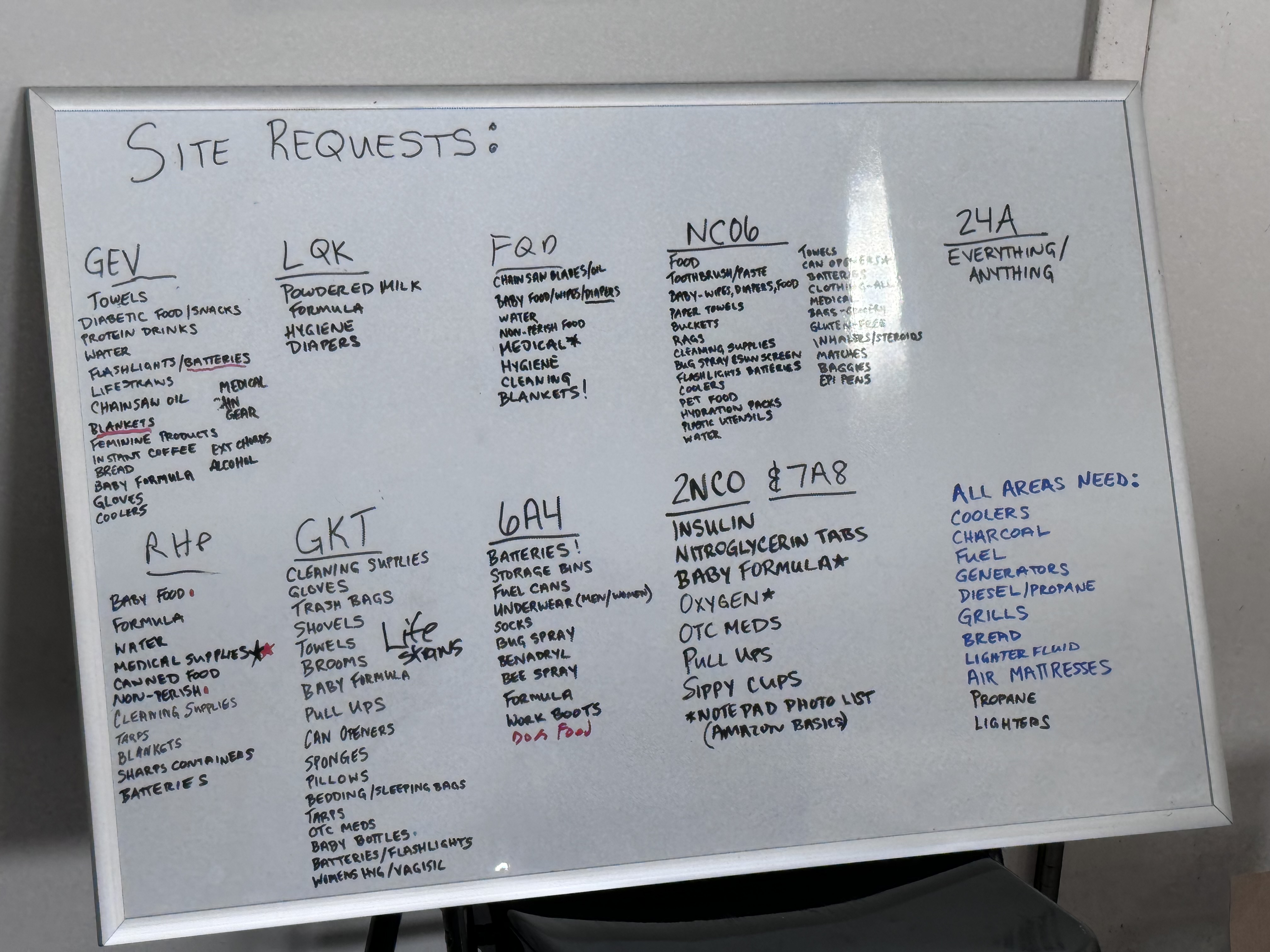

Dispatch was trying to get supplies to where they were needed, they used this whiteboard to keep track of who needed what:

You can kinda tell from the photo above which areas were further along in their recovery. Because communications were often cut off (depended on the area), a lot of this information was relayed by the pilots returning from supply runs.

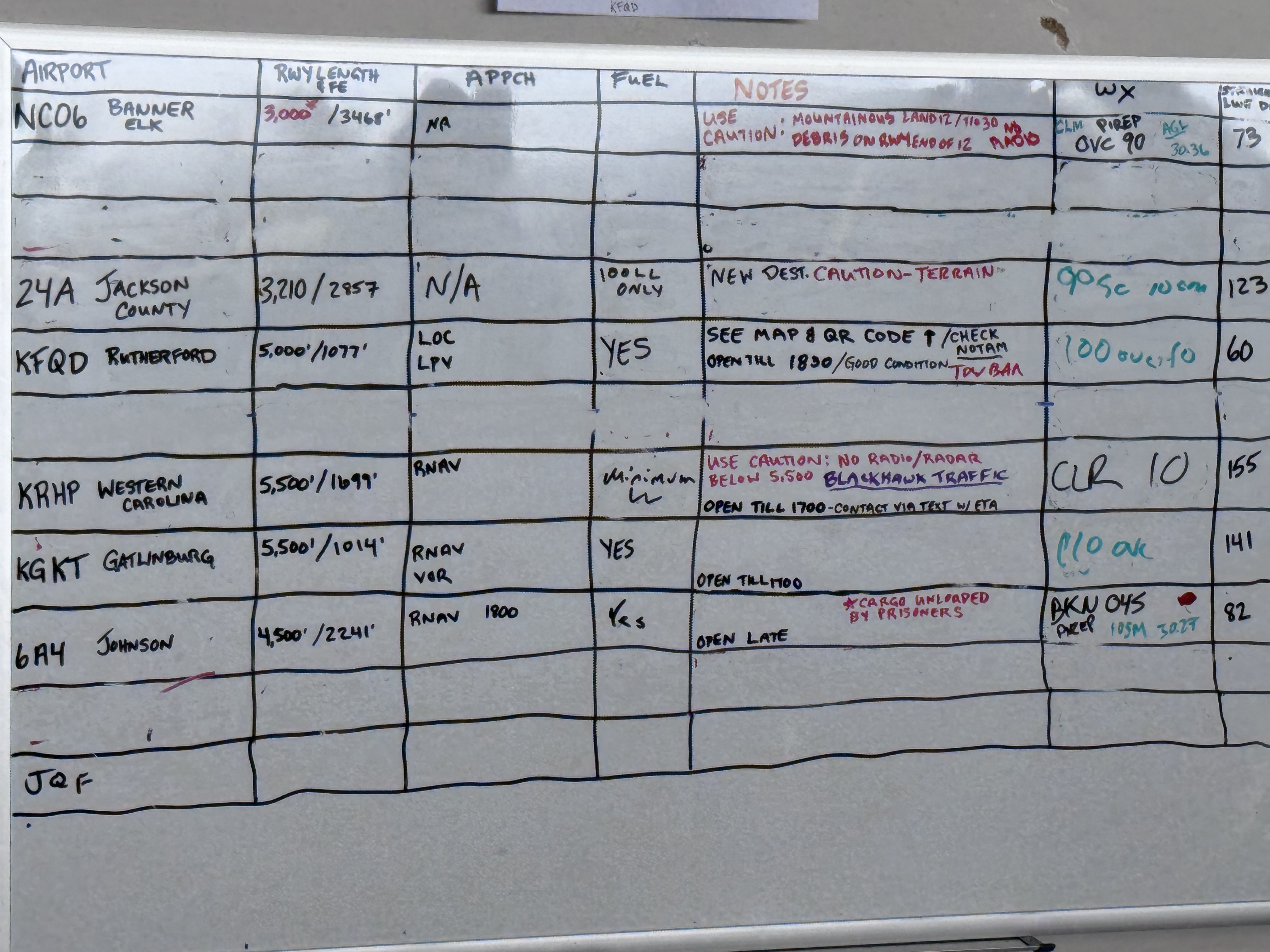

Similarly runway/weather/airport conditions were tracked as well:

Not every airport is there (mine wasn’t) because this dispatcher hadn’t yet received word (it turns out that other orgs had made supply runs there, this dispatcher just hadn’t known about that).

Volunteers had pre-weighed pallets of supplies. Depending on where you were going and how much you could carry, you’d pick a pallet to be loaded into the aircraft. Volunteers helped at each stage of this process, including loading the cargo.

At no point did anyone from the FAA or FEMA get in the way of this process (a claim being made online).

Supply Run

The tower at the supply hub was so wildly busy and they were working magic. They did a fantastic job of getting everyone off the ground in a timely manner. As one aircraft was waiting on an IFR clearance, and they had me taxi through the grass in order to depart earlier since I was flying VFR. Not really the behavior of someone trying to prevent people from helping.

On the way to my destination ATC was great again. The approach and landing went as briefed, we had to descend into a valley, which is always a bit spooky as it means there is terrain higher than you as you come in for a landing, leaving you with fewer options if things go poorly. While it was uneventful, the pre-planning was absolutely necessary as it was tricky and full of obstacles.

The folks on the ground there helped me unload the plane and had special requests for aid. They asked me to communicate those requests back to dispatch. On the way back to the supply hub I had a very close call with another aircraft1. Normally ATC would have given me a heads up, but they were so swamped. Weather was getting worse too, which caused congestion of VFR aircraft since we all had to find visual paths around clouds and holes through layers for descent.

Unfortunately the weather prevented further supply runs to that area. Luckily (though I did not know this at the time), the roads opened up to that area later that day, which is great news.

The issues on the ground are that the infrastructure has been destroyed, communication is difficult, and the environment is changing all the time: some roads reopen, which shifts where aircraft are actually needed, etc. All of these are difficult coordination problems and there are many cooks in the kitchen; all well-meaning and all trying their best.

I want to reiterate because it’s by far the largest discrepancy between what I experienced and what I’m reading on the internet: at no point was the government ‘in my way’. It’s just a very difficult overall situation! When ATC closes off a part of airspace it’s not to prevent people from trying to help, it’s because when the weather is getting worse they have to close off airspace so that larger supply aircraft can navigate safely without risk of midair collision.

I was sad that I could not do more, and that I hadn’t gone earlier in the week. That said, it was gratifying to be able to help, even if it was a small help.

I have immense respect for those working ATC and folks doing supply runs over multiple days.

-JMCT

I have since filed a NASA ASRS report about the incident to help prevent similar incidences in the future.↩